The Supreme Court found that the U.S. Government breached a commitment to Pay $12 Billion to Health Insurers, but are these payments going to help beneficiaries?

Introduction

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled on three cases brought by four insurers over whether insurers are entitled to $12.3 billion in unpaid risk corridors payments from 2014 to 2016. The reactions to the ruling mostly fell along political party lines. This article presents questions and objective data to consider.

Objective View and Issues

Did the Government make a promise to pay $12.3 billion to health plans and then break that promise? According to the Ruling by The U.S. Supreme Court, the answer is yes. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor stated, the ruling is based on “a principle as old as the nation itself: the government should honor its obligations.” Insurers will receive billions in unpaid risk corridors payments, but it could take time for these funds to flow to insurers. And the impact of this decision will vary significantly by state and insurer. Were these extra protections necessary for insurers? Do they increase competition in the Insurance Exchanges? Do they benefit consumers?

Risk Corridor Litigation Timeline

- 2014 to 2016 – The litigation involved an estimated $12.3 billion in accumulated risk corridor funds accrued from 2014 to 2016 that were not paid out to insurers.

- June 14, 2018 – the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled against health plans seeking risk corridors payments from the Federal Government. The lawsuit, Maine Community Health Options v. the United States, stems from three consolidated cases: Maine Community Health Options, Moda Health Plan, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina, and Land of Lincoln Mutual Health Insurance Company. This ruling was appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

- December 10, 2019 – The Supreme Court of the United States heard an oral argument over whether insurers are entitled to more than $12 billion in unpaid risk corridor payments.

- April 27, 2020 – The Supreme Court issued its decision in Maine Community Health Options v. the United States. Justice Sonia Sotomayor wrote the opinion for the Court on behalf of the 8 to 1 majority, concluding that insurers are owed unpaid risk corridor payments and reversing the Federal Circuit’s ruling. The Court held that Section 1342 of the Affordable Care Act established a money-mandating obligation, that Congress did not repeal this obligation using appropriations riders, and that the insurers could sue the federal Government for owed payments. Only Justice Alito dissented. Justices Clarence Thomas and Neil Gorsuch joined most, but not all, of the majority opinion.

History of Risk Corridors in the Affordable Care Act

The individual (or “non-group”) insurance market changed substantially under the Affordable Care Act. In 2014, the Affordable Care Act instantiated new rules delineating: 1) the type of plan that can be sold, 2) required insurance companies to guarantee access to everyone regardless of health status, and 3) limited the factors insurers could use in setting premiums. Before that, fissures in public insurance and deficiency of access to affordable private coverage left millions of Americans without health insurance. The Affordable Care Act filled in many of these gaps and provided new coverage options via Health Insurance Exchanges (HIEs). HIEs were designed to enable consumers to obtain federal tax credits to help them pay their premiums.[1]

Because of the new rules promulgated by the Affordable Care Act, insurers did not have the requisite actuarial experience to accurately estimate the newly insured’s use of medical services. The Affordable Care Act requires that insurers must file their rates roughly 18 months prior to the end of the following rating year.[2] Therefore, decisions made in 2014 by health plans had consequences in 2016. Also, in 2015 and 2016, there was substantial turnover among insurers in the individual market, as some initial players learned that they were not able to compete effectively under the new market rules.[3]

The Affordable Care Act included risk-mitigating measures to protect the health plans, known as:

- reinsurance,

- risk-adjustment, and

- risk corridors.[4]

Risk corridors were intended to limit both the amount of money that a health insurance plan can make — and how much it can lose — during the first three years, it sells on the health insurance exchanges. In part, the intent was to encourage insurers to enter the HIE markets by mitigating their risk, or “…to protect against the effects of adverse selection…”

Risk corridors were intended to be a temporary feature applied to individual, and small group qualified health plans (QHP) from 2014 to 2016. Risk corridors only applied to plans sold on the Exchanges via HIEs.

How Risk Corridor Calculations Work

Risk Corridors may look like a viable downside mitigation mechanism, but the devil is in the detail. According to the Affordable Care Act, HHS Notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters for 2014 Final Rule,[5] the steps involved in a risk corridor calculation are below. The critical component is to note that “MLR” or Medical Loss Ratio is a factor. It will become clear why MLR is essential later in this article.

Risk corridor ratio = Allowable costs / target amount

Defined values: Claim Costs, IBNR, Allowable Costs, Quality Expenses, Healthcare IT, MLR reference, Profits, Premium, non-claim costs, floors, after-tax premiums, Administrative Costs, Allowable Administrative Costs, Target Amount and Premium Charged.[6]

- Claim costs = Incurred claims + (incurred but not reported ‘IBNR’[7] claims) + payments/receipts from risk adjustment and transitional reinsurance.

- Allowable costs = Claim costs + quality expenses [8] + health care information technology [9] (consistent with the medical loss ratio (MLR) definition).

- Profits = (Premium – allowable costs – non-claim costs), floored at 3 percent of the after-tax premium.

- Administrative costs = Non-claim costs – taxes/ fees.

- Allowable administrative costs = Taxes/fees + (administrative costs + profit, capped at 20 percent of after-tax premium)

- Target amount = Premium charged – allowable administrative costs.

The program required profitable insurers to pay funds into the program and used these funds to subsidize insurers with higher medical claims. Congress subsequently inserted riders in appropriations legislation, which made the risk corridor program budget neutral—meaning the program would not pay out more money than it received.[10]

Risk Corridor Controversy

The risk corridor program created by the Affordable Care Act is one of the most complex and debated aspects of the health care law. HHS indicated that it believes it has a duty under section 1342 of the Affordable Care Act , which establishes the risk corridor program and requires HHS to collect payments from and make payments to specific qualified health plans.

The first risk corridor payments were not due until the 2015 fiscal year. The Consolidated and Further Continuing Appropriations Act of 2015, which funded the Government for the 2015 fiscal year, did not eliminate the risk corridor program, nor did it prevent HHS from using payments received from insurers to pay out claims under the program.

Risk corridors protect insurers, but the accompanying rules of the Affordable Care Act do not consider the funds that insurers spend for:

- Fraud & abuse detection and prevention

- Cost containment management activities

- Broker commissions that are bundled with premium

The logic is that the inefficiencies of fraud, waste, and abuse that go into the risk corridors are a cost of doing business. Therefore, insurers are not allowed to include the costs to prevent fraud in their cost formulas. Yet, American taxpayers are backstopping insurance company losses, which can be caused in part by fraud. Here is how this conundrum came about. it is estimated that Medicare fraud is significant. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid stated in 2020:

“The FY 2020 Medicare FFS estimated improper payment rate is 6.27 percent, representing $25.74 billion in improper payments. This compares to the FY 2019 estimated improper payment rate of 7.25 percent, representing $28.91 billion in improper payments.“

Expected Benefits to the Consumer via Market Competition

Using Medicare Part D as a Basis

Some have argued that the most crucial benefit of risk corridors was to consumers. Risk corridors, so the logic goes, were intended to encourage small insurers to participate in the healthcare marketplaces to provide competition to large insurers. When the risk corridor payments were withheld, some small insurers lost money, exited the marketplaces, or went out of business. This allegedly caused harm to the consumer. Supporters of risk corridors have pointed out that Medicare Part D adopted risk corridors under the Republican Bush Administration. As one supported noted, “ Medicare’s successful prescription drug coverage program (Part D) also uses risk corridors – and if the most recent [2012] trustees report is to believed (see Table IV.B11), Part D’s risk corridors are far from a bailout for insurers. …” Comparing 2013 actuarial data to 2018, the picture looks quite different. See the Actuarial Analysis in the next section.

Actuarial Analysis of Costs and Benefits to Consumers and the Government in Plans with Risk Corridors

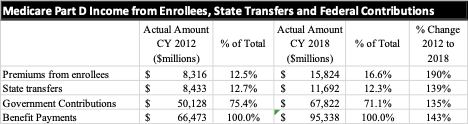

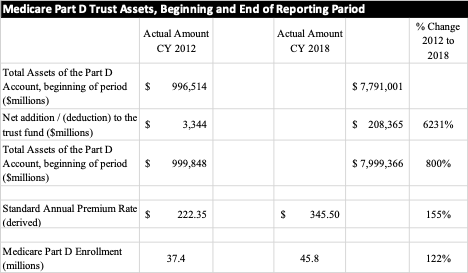

Based on reports from the Secretary of the Treasury and in the Annual report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds:[11], [12]

- Total premiums received from Medicare Part D enrollees increased 190%

- Yet, Federal Government contributions decreased as a percent of total contributions from 75.4% to 71%

At first glance, it might appear that the Government, and therefore taxpayers are not contributing as much to Medicare Part D in 2018 as they did in 2012. Unfortunately, costs to the consumer have increased 155% as the derived standard annual premium rate increased during the same period. So, objective data suggests that Medicare Part D is not a model of success for risk corridors in that it has neither lowered costs to the taxpayer or to the consumer.

Figure 1 – Summary of change in premiums from enrollees, state transfers, Federal Government contributions, and benefits payments, CY 2012 vs. CY 2018

Figure 2 – Summary of change in assets and additions to the Medicare Part D trust find, standard annual premium rate, and Part D enrollment CY 2012 to CY 2018

Therefore, in the end, the consumer did not benefit from risk corridors in Medicare Part D. Under the insurance market where there is not a single-payer system as there is with Medicare Part D, could the outcome be different? Next, take a look at the inefficiencies legislated into the Medical Loss Ratio rules for commercial plans available on the Exchanges.

Affordable Care Act Established Medical Loss Ratio (MLR)

Every year, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services loses an estimated $65 billion to criminals who defraud the health care system.[13] This excludes fraud losses incurred by commercial payers who offer coverage in the Health Insurance Exchanges.

Section 2718 of the Affordable Care ACt established medical loss ratio (MLR) minimums establishing a minimum floor on the percent of premium collected that is spent on providing medical services and improving the quality of care.

Under the Affordable Care Act , insurers must spend a certain percentage of their premium revenue—80 percent in the individual and small group markets and 85 percent in the large group market—on health care claims or health care quality improvement expenses. The remainder of the premium revenue can go towards other expenses, such as administrative expenses, profit, and marketing.

If insurers fail to meet an MLR of 80 or 85 percent (meaning they spend too little of their premium revenue on health care claims or quality improvement), they must rebate the difference to their enrollees.[14] Health plans must spend on a combination of reimbursement for medical services and “activities that improve health care quality.”[15] The ACA’s MLR rule took effect in 2011.[16]

Expenditures to Control or Contain Costs Such as Fraud are Excluded from MLR

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS) provides: “The list of activities excluded as QIA includes—(1) Those activities designed primarily to control or contain costs; and (2) those that establish or maintain a claims adjudication system, including costs directly related to upgrades in HIT that are designed primarily or solely to improve claims payment capabilities or to meet regulatory requirements for processing claims…”.[17] MLR rules hamstrung health plans by preventing them from including expenses in the MLR calculation designed to modernize their computing systems, make them compliant to new Standards, and to avoid fraud. As noted above, the MLR calculation and its limitations are used in the risk corridor calculations.

Conclusion

In his dissent of the U.S. Supreme Court opinion, Justice Samuel Alito said the decision is a massive bailout “for insurance companies that took a calculated risk and lost. These companies chose to participate in an Affordable Care Act program that they thought would be profitable.” Alito stated that he believes that the opinion is a bailout for health plans. At the very least, this bailout to health plans should include provisions for greater efficiencies and anti-fraud. Clearly, efforts of health insurers to reduce fraud are “activities that improve health care quality.” How could this be implemented?

- Objective data regarding insured beneficiary premium and out-of-pocket costs as well as healthcare utilization.

- By removing the exclusion of fraud prevention from the definition of QIA and expanding the definition of QIA to include all fraud reduction activities. Without better methods to pursue fraud, including modifications to MLR and QIA, health plans may not be using the $12.3 billion to benefit the populations they insure – or, indeed, not as efficiently as they could.

Michael F. Arrigo is the CEO of No World Borders, a healthcare data regulations and economics firm. He serves as an expert witness regarding the Affordable Care Act. He has served as an expert witness regarding risk adjustment in Medicare fraud cases involving patient diagnoses, HCC coding and various risk models.

Citations

[1] Has the Individual Market Grown under the Affordable Care Act? Kaiser Health News. https://www.kff.org/health-reform/issue-brief/data-note-how-has-the-individual-insurance-market-grown-under-the-affordable-care-act/

[2] CMS Center for Consumer Information & Insurance Oversight, The 80/20 Rule, 2016. https://www.cms.gov/CCIIO/Resources/Forms-Reports-and-Other-Resources/mlr-rebates06212012a

[3] Ashley Semanskee et al., Insurer Participation on ACA Marketplaces, 2014–2018 (Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, Nov. 2017); and Craig Garthwaite and John A. Graves, “Success and Failure in the Insurance Exchanges,” New England Journal of Medicine 376, no. 10 (Mar. 9, 2017): 907–10.

[4] David Blumenthal, “The Three R’s of Health Insurance,” To the Point (blog), Commonwealth Fund, Mar. 5, 2014.

[5] U.S. department of Health and Human Services Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act; HHS notice of Benefit and Payment Parameters for 2014 (Final Rule). Federal Register, Vol. 78, no. 47, 45 CFR Parts 153, 155, 156, 157 and 158, p. 15516. Retrieved July 12, 2013, from http:// www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2013-03-11/pdf/2013- 04902.pdf

[6] 2013. Doug Norris, Mary van der Heijde, Hans Leida. Health Watch – Risk Corridors under the Affordable Care Act – A Bridge Over Troubled Waters, but the Devil’s in the Details. Society of Actuaries.

[7] IBNR is an estimate of the amount of claim dollars outstanding for events that have already happened but have not yet been reported to the risk-bearing entity

[8] Note that Allowable Costs include quality expenses and IT expenses but is based on the same MLR standard and therefore excludes expenses to pursue fraud as discussed in the MLR section of this document.

[9] Id.

[10] Xavier G. Hardy. Appeals Court Rejects Insurers Risk Corridors Claims https://www.mintz.com/insights-center/viewpoints/2146/2018-06-appeals-court-rejects-insurers-risk-corridors-claims

[11] CY 2012 data: Part D Financial Status, 2013 Annual report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-https://downloads.cms.gov/files/TR2013.pdf

[12] CY 2018 data: Part D Financial Status, 2019 Annual report of the Boards of Trustees of the Federal Hospital Insurance and Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust Funds. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/Downloads/TR2019.pdf

[13] Kaiser Health News and the National Healthcare Anti-Fraud Association https://khn.org/saccocio-medical-fraud/

[14] The Medical Loss Ratio provision requires insurance companies that cover individuals and small businesses to spend at least 80% of their premium income on health care claims and quality improvement, leaving the remaining 20% for administration, marketing, and profit. The MLR threshold is higher for large group insured plans, which must spend at least 85% of premium dollars on health care and quality improvement. Insurers failing to meet the applicable MLR standard have been required to pay rebates to consumers since 2012 (based on their 2011 experience). Currently, MLR rebates are based on a 3-year average, meaning that 2020 rebates are calculated using insurers’ financial data in 2017, 2018, and 2019. Insurers may either issue rebates in the form of a premium credit or a check payment and, in the case of people with employer coverage, the rebate may be shared between the employer and the employee. Insurers will begin issuing rebates later this fall. Rebates issued in 2020 will go to subscribers who were enrolled in rebate-eligible plans in 2019. See https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/issue-brief/data-note-2020-medical-loss-ratio-rebates/ and https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20200427.34146/full/

[15] Loss ratios based on a calculation using a three-year rolling average, meaning that the regulatory standard is applied each year to the insurer’s average loss ratio during the prior three years.

[16] Michael J. McCue and Mark A. Hall, The Federal Medical Loss Ratio Rule: Implications for Consumers in Year 3 (Commonwealth Fund, Mar. 2015).

[17] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) Medical Loss Ratio (MLR) Annual Reporting Form Filing Instructions for the 2015 MLR Reporting Year