Medicare LCDs

Medicare Local Coverage Determinations (LCDs) are inconsistent and cause uneven access to care for Medicare beneficiaries based on arbitrarily geographic boundaries and jurisdictions, rather than on medical necessity. That is the finding from none other than the Federal Government. The U.S. Health and Human Services (HHS) Office of Inspector General (OIG) published a report stating this embarrassing conclusion for the Medicare program.

For more than thirty-four years (1984 to 2018), several cases have identified the need to remove ambiguity from Medicare regulations and Coverage Determinations. For example, in 1984 in Heckler v. Ringer attorney Edwin Kneedler (Deputy United States Solicitor General) presenting before the U.S. Supreme court [i] said,

“There is a pressing need in this area involving many claims for the Secretary and the courts to have clear rules that can be easily and uniformly applied in all cases without the need to litigate in particular cases their applicability, and the rules the Secretary and Congress have established for this purpose are fair and reasonable.”[ii]

Thirty years later, the U.S. HHS OIG stated,

“LOCAL COVERAGE DETERMINATIONS CREATE INCONSISTENCY IN MEDICARE COVERAGE”

(See Daniel R. Levinson Inspector General January 2014 OEI-01-11-00500)

According to the U.S. HHS OIG report in 2014:

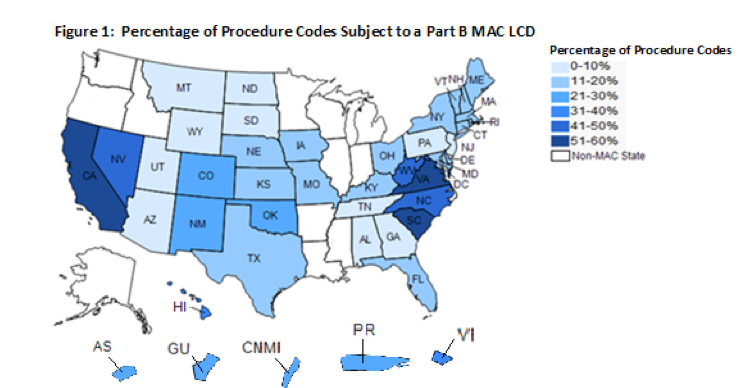

A. LCDs limited coverage for these procedure codes differently across States.

“Medicare had at least two different coverage policies for the 59 percent of procedure codes subject to LCDs. All but two of these procedure codes were subject to one or more LCDs that limited coverage in some, but not all States. Thus, coverage for a given service may be restricted in one State where an LCD is in place and completely unrestricted in another State where no LCD is in place. The remaining two procedure codes were subject to LCDs in all States. However, the LCDs for these procedures created different coverage policies that could vary from State to State. MACs may have developed LCDs for these procedure codes to address situations in their local jurisdictions, including overuse or misuse of items or services. (See page 9 LOCAL COVERAGE DETERMINATIONS CREATE INCONSISTENCY IN MEDICARE COVERAGE Daniel R. Levinson Inspector General January 2014 OEI-01-11-00500).”

B. LCDs prohibited coverage for some procedure codes—often those for new technology—in some States and not in others. “LCDs prohibited coverage for 467 procedure codes for Part B items and services in one or more States. However, out of the 467 codes, 187 (40 percent) had allowed charges in one or more States where LCDs did not prohibit coverage. These allowed charges totaled $9.7 million during the 1-week period we reviewed or about $500 million yearly. As a result, beneficiaries in some States did not have access to items and services that had significant use among beneficiaries in other States. (See page 9 LOCAL COVERAGE DETERMINATIONS CREATE INCONSISTENCY IN MEDICARE COVERAGE Daniel R. Levinson Inspector General January 2014 OEI-01-11-00500).”

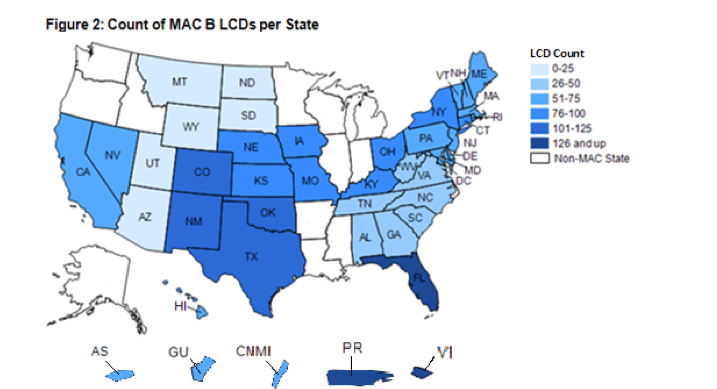

Virgin Islands. These three States are all within the same MAC jurisdiction and one—Florida—contains two cities targeted by the Medicare Strike Force because of high levels of Medicare fraud. Conversely, some other States had as few as 25 LCDs that restricted coverage for items and services. Therefore, the likelihood that beneficiaries’ items and services had coverage restrictions placed on them by LCDs varied widely by State

C. Additionally, LCDs were concentrated in several States. “Over a fifth, or 236, of the 1,131 LCDs in effect during our review restricted coverage for items and services in only 3 geographic areas—Florida, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. These three locations are all within the same MAC jurisdiction and one—Florida—contains two cities targeted by the Medicare Strike Force because of high levels of Medicare fraud. Conversely, some other States had as few as 25 LCDs that restricted coverage for items and services. Therefore, the likelihood that beneficiaries’ items and services had coverage restrictions placed on them by LCDs varied widely by State (See page 11 LOCAL COVERAGE DETERMINATIONS CREATE INCONSISTENCY IN MEDICARE COVERAGE Daniel R. Levinson Inspector General January 2014 OEI-01-11-00500).”

LCDs defined similar clinical topics inconsistently

Out of the 540 clinical topics addressed by LCDs, none were addressed by an LCD in every State—meaning that every clinical topic was addressed in some states but not others. LCDs address a specific clinical topic, such as interventional cardiology, by listing the procedure codes that define a particular treatment and the diagnostic codes that describe the covered indications for the treatment. Therefore, Medicare defines how and under what circumstances beneficiaries have access to certain treatments in some States (where an LCD exists), but not in others (where an LCD does not exist).

A total of 319 of the 540 clinical topics, or 59 percent, were addressed by more than one LCD; however, 134 were addressed inconsistently among LCDs. This means that different LCDs used different procedures and/or diagnostic codes to address the same clinical topic. One example is blepharoplasty—surgery to correct drooping eyelids that impair vision. At the time of our review, LCDs addressed blepharoplasty in 32 of the

CMS has taken steps to increase consistency among LCDs, but it lacks a plan to evaluate new LCDs for national coverage as called for by the MMA

CMS convenes several workgroups among the MACs that collaborate on discrete topics such as molecular diagnostic services and self-administered drugs. It also supports in-person meetings of the LCD Writers’ Group, coordination calls among MAC medical directors, and a listserv for MAC medical directors to share information. Together, these activities have the potential to increase consistency among LCDs, but they do not represent a plan for evaluating new LCDs for national coverage.

To evaluate new LCDs for national coverage, CMS established the 731 Advisory Group and a review process in the Medicare Program Integrity Manual. 23 CMS defined (1) criteria that contractors’ medical directors should use to evaluate topics to submit to the 731 Advisory group, (2) the role of the 731 Advisory Group, and (3) steps that CMS would take concerning reviewing, tracking, and evaluating topics put forth for NCD consideration.

However, the 731 Advisory Group was either never convened or was disbanded when CMS shifted responsibility for LCDs within the agency. Thus, CMS was unable to quantify the results of the group or locate agendas and minutes of the group’s meetings and calls. The 731 Advisory Group and the related framework for reviewing LCDs for national coverage remain in the Medicare Program Integrity Manual.

Finally, according to the OIG report, CMS was unable to quantify the results of the LCD Writers’ Group fully and only provided examples of NCDs resulting from the group in its technical comments to our draft of this report. Although CMS was able to provide agendas from the group’s meetings, it did not keep minutes of these meetings.

See OFFICE OF INSPECTOR GENERAL. https://www.oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-01-11-00500.pdf

[i] Edwin Kneedler found a career arguing cases before the Supreme Court Washington Post https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/courts_law/edwin-kneedler-found-a-career-and-a-calling-arguing-before-the-supreme-court/2014/09/10/bfde2bc6-345a-11e4-9e92-0899b306bbea_story.html?utm_term=.6f676d29bbc3

[ii] Heckler v. Ringer Oral Argument – February 27, 1984, https://www.oyez.org/cases/1983/82-1772

Related Posts and topics

Medicare Part D Expert Witness

Medicare Part C Risk Adjustment